So for now: reading!

HIGHLIGHTS AND GENERAL REFLECTIONS

2018 was a big year for me:

Those traits are also to be found in three of my favorite longer novels for the year: Rabih Alameddine's The Angel of History (a tragicomic lament for the narrator's friends, lover, culture, and city, lost to the AIDS epidemic and gentrification); Barbara Browning's The Gift (a meditation on fidelity, intimacy, and the ethics of transforming life into art); and Sarah Schulman's Maggie Terry (an ostensible detective novel that is really more about examining the process of recovering from addiction). Other novel highlights include Laura van den Berg's The Third Hotel, a feminist take on the Lynchian plot where a possibly-unreliable narrator pursues someone who they may or may not actually know through a foreign landscape; and Samantha Schweblin's Fever Dream, an intensely claustrophobic and well-rendered novella about parenthood, secrets, and contamination. I haven't finished it yet, but Carol Bensimon's We All Loved Cowboys, a queer female Brazilian roadtrip story, may end up on the highlights list as well.

I also ended up doing something this year that I haven't done a lot of before (or at least, not since college), which is to read multiple works by the same person back-to-back or in close succession. Specifically, this year brought me Soucouyant and Brother by David Chariandy; Maggie Terry and The Gentrification of the Mind by Sarah Schulman; and Crudo and The Lonely City by Olivia Laing. This was a totally unplanned side effect of my transition to using the library app Libby for a lot of my reading: in all three cases, the book I'd originally been interested in was unavailable, so I read another by the same author while waiting for my hold to come in. But ended up being an illuminating exercise. The Chariandy novellas are basically two takes on the same story (a young Black man returns to his old Toronto neighborhood during the last weeks of the life of his mother, who has suffered from dementia since before he left home), but their foci were different enough that I felt like they gained by being read back-to-back, rather than becoming repetitive. In the cases of Schulman and Laing, their nonfiction book spoke very directly to their fiction (in Schulman's case EXTREMELY directly), which made my reading experience of both more multifaceted.

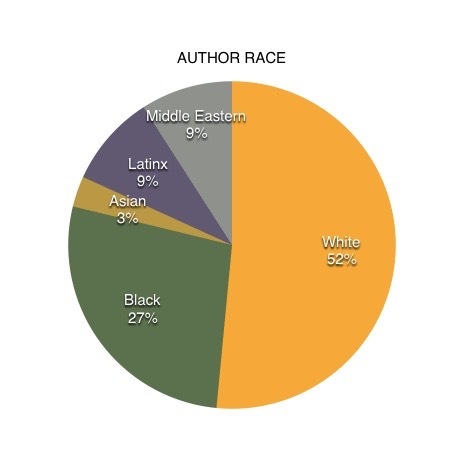

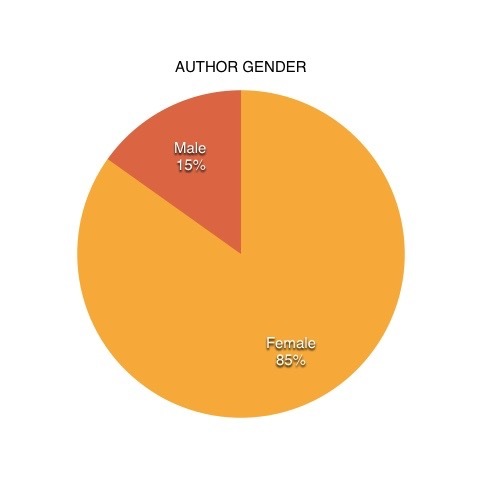

Another thing that set 2018 apart, reading-wise, was my year-long pledge to read zero books by white men. I kept to this pledge, which was an interesting experience though not in quite the way I'd anticipated... which I'll go into more in the Race and Gender section below. In all of the following sections, there are reflections under the cut links.

( Format )

( Genre )

( Race and Gender )

( Queerness in the text, and Author Nationality )

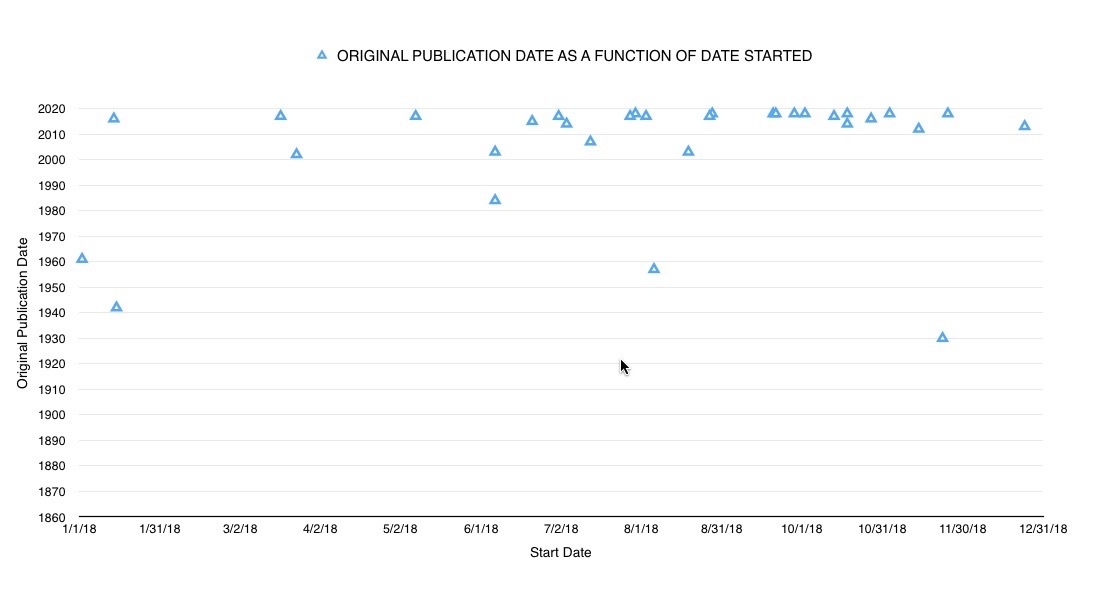

( Original Pub Date as a function of Date Started )

Gathered from the above, reading goals for 2019 include:

- Dedicate time in the evenings for reading books not on my phone

- Research newsletters or other news sources on new literary translations from non-US countries [edit: Asymptote, which is run out of London, has a fortnightly newsletter on world literature in translation. Three Percent has a few podcasts but seemingly no newsletter (sadly I'm just... not gonna get around to podcasts). They do have a book review category and a Best Translated Book Awards category.]

- Research newsletters or other news sources on country- or region-specific new releases

- Read a larger percentage of books from countries other than the US

- Read a larger percentage of books by people of color

- Also, I've made this goal for the past few years and haven't delivered, but: read a novel in French! I have a whole shelf to choose from.